Rickwood Field’s legendary history: How Willie Mays and the Negro Leagues made the iconic stadium home

Written by CBS SPORTS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED on June 19, 2024

It is older than both Wrigley Field and Fenway Park – indeed it is the oldest venue for professional baseball in the United States. It is one of two remaining Negro League parks. It has – in a testament to its historical breadth – hosted within its walls 181 of the 351 total Hall of Famers, whether players, managers or operators of teams. On the playing side, the list includes true pantheon dwellers of the sport: Willie Mays, Satchel Paige, Hank Aaron, Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Honus Wagner, Cool Papa Bell, Ted Williams, Joe DiMaggio, Rogers Hornsby, Reggie Jackson, Stan Musial, Ernie Banks, Dizzy Dean, Rollie Fingers.

Of these, Mays, perhaps the greatest baseball player in the annals of baseball players, is the Hall of Famer most linked with Rickwood Field. Mays, who died Tuesday, was a native of the Birmingham, Ala., area, and so he was on his hometown field when he suited up for the Birmingham Black Barons in 1948. It was Mays’ first season as a professional and the start of a career that would tower over that of almost any other player. It’s fitting, then, that when Mays’ former team, the Giants, takes the field against the Cardinals on Thursday in Birmingham, it’ll be a celebration not only of Mays but also of the setting – the living museum that is Rickwood Field.

Major League Baseball’s foray into Rickwood also marks the latest initiative to embrace – or co-opt, if you find that term more accurate – the history of the bygone Negro Leagues. For MLB, it’s a complicated needle to thread, which, frankly, it should be. Only because of organized baseball’s racist and segregationist policies did the Negro Leagues ever exist, just as only because of those policies was Jackie Robinson tasked with shattering them. However, ignoring the Negro Leagues, even if done so out of a sense of institutional modesty or chagrin over MLB’s foundational moral failings, probably wasn’t tenable.

The first major step of recent years came in December 2020, when MLB, officially and from on high, recognized the Negro Leagues during the 1920-48 period as being of “major league” status. The leading practical effect of this elevation is that the more than 3,000 players who appeared in the Negro Leagues during that time became Major Leaguers in the official record. The decision reversed and belatedly corrected that of a 1969 league committee that bestowed major-league status upon multiple circuits from the early days of organized baseball but not the Negro Leagues.

The next and most recent sea change came earlier this year, when the league incorporated Negro League statistics into MLB’s official stats. This of course carried with it many implications, many of which are sweeping in nature. For prominent instance, the luminous Josh Gibson is now the all-time leader in a number of batting categories. More to the point of this endeavor, Mays picked up 10 hits thanks to his efforts for the ’48 Black Barons.

This brings us back to Thursday’s celebration of Mays, Rickwood Field, and the Negro Leagues. While Mays’ death now puts a somber shadow over the event, it nevertheless promises to be a compelling and important evening of baseball between the contending Giants and Cardinals. No matter how the game on the field plays out and who authors the outcome, the star will be Birmingham’s Rickwood Field, which will at last receive a wide-scale appreciation of its history, beauty, and importance.

To add to that appreciation, we’ve put together a historical timeline of Rickwood Field. The hope is that what follows hints at the historical sprawl of the ballpark and its necessary place of honor in the story of baseball.

February 1910

Soon after millionaire industrialist A.H. “Rick” Woodward buys controlling interest in the Southern Association’s Birmingham Barons, he sets about building the first concrete-and-steel ballpark in the minors. Woodward models the park after Shibe Park in Philadelphia and Forbes Field in Pittsburgh and undertakes the project after consulting with Connie Mack of the Athletics, who visits Birmingham. Woodward brands it as “The Finest Minor-League Ballpark Ever.” Initially projected to cost $25,000, the venue in the end carries a price of three times that figure.

Aug. 18, 1910

Rickwood Field, named for Woodward, opens in Birmingham, and city businesses close for the day to mark the occasion. Rickwood, nestled on a 12.7-acre plot at 2nd Avenue West and 12th Street West, has an official seating capacity of 5,000, but a crowd of more than 10,000 (12,000 by some estimates) turns out for the first game, thus setting a Southern League attendance record. Woodward himself suits up, puts himself in the lineup and throws out the first pitch – the first game pitch, not a ceremonial first pitch (it’s a ball). He then watches the remainder of the game from the stands. which the Barons win over Montgomery 3-2 in walk-off fashion.

The park features a basketball hoop on a Mellow Yellow sign in right-center. Any player to hit a ball through the hoop is promised $500, but no one ever succeeds.

Soon after “Shoeless” Joe Jackson, later to be permanently banned for his alleged role in the Black Sox Scandal, plays at Rickwood as a member of the visiting New Orleans Pelicans.

1911

The University of Alabama and Auburn University football teams begin to use Rickwood as a site for home games. They will do so until 1927.

1912

Player-manager Carlton Molesworth guides the Barons to their first league title since Rickwood Field opened.

1915

Rickwood Field hosts a one-inning “Suffrage Day” exhibition in which the players are women advocating for the right to vote.

1920

The Birmingham Stars of the Negro Southern League become a tenant at Rickwood Field and are soon renamed the Birmingham Black Barons. For the next 40 years, the Black Barons and the Barons will share Rickwood Field, although, in keeping with the racial barriers of the times, never play against each other.

April 16, 1921

An early morning tornado strikes Rickwood Field and causes $30,000 in damage.

1923

The Black Barons are promoted to the major-league Negro National League, first as an associate franchise and then by 1925 as a full member of Rube Foster’s circuit. Mule Suttles, a 23-year-old left fielder and first baseman, emerges as their first star after joining the NNL.

Rickwood proves to be an alluring venue for the many barnstorming teams around the country. Early big names to visit Rickwood as barnstormers include Ty Cobb and Rogers Hornsby.

Mid- to late-1920s

As part of a larger complement of renovations, the steel infield grandstand at Rickwood is extended to provide more shade to fans in the right-field bleachers.

1927

The 20-year-old rookie right-hander Satchel Paige helps the Black Barons to the postseason.

1929

Touring with the Yankees, Babe Ruth makes an appearance at Rickwood.

1928

A facade styled like a traditional Spanish mission is constructed at the entrance to the park. As well, a new scoreboard in left field is added. The scoreboard will later be relocated to right field.

1930

Paige leaves the Black Barons to join the Cleveland Cubs.

1931

Brought low by the Great Depression, the Black Barons drop back to the Negro Southern League.

Autumn 1931

Widely regarded as the greatest game ever played at Rickwood Field, 20-year-old Dizzy Dean and the Houston Buffaloes fall 1-0 to 43-year-old Ray Caldwell and the Barons in the Dixie Series. An overstuffed crowd of more than 20,000 witnesses the classic.

1936

Night baseball comes to Rickwood after four 75-foot, steel-frame light towers are built around the field. For four seasons around this time, Bull Connor serves as the Baron’s play-by-play broadcaster. Connor will later earn infamy as Birmingham’s segregationist commissioner of public safety and sworn enemy of the Civil Rights movement.

1937

The Black Barons return to the highest level of Black baseball as members of the Negro American League.

Feb. 7, 1939

Woodward sells the Barons to local businessman Ed Norton for $175,000.

1940

Rickwood Field’s seating capacity is expanded to 15,000.

1942

College football returns to Rickwood Field with the Vulcan Bowl, the Negro College Football Championship.

1943

The Black Barons advance to their first Negro League World Series but fall in six games to the Homestead Grays.

1944

The Black Barons are again Negro American League champions but again they fall to the Homestead Grays in the Negro League World Series.

April 15, 1947

Jackie Robinson breaks Major League Baseball’s color barrier when he debuts for the Brooklyn Dodgers. This watershed moment and the subsequent drift of Black baseball talent to organized baseball will lead to a fairly sudden undermining of the Negro Leagues’ viability as a business.

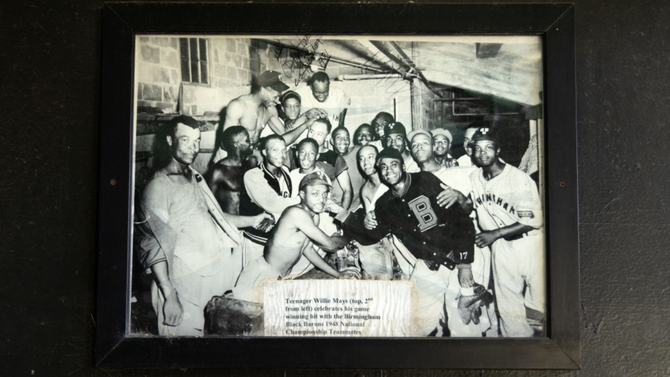

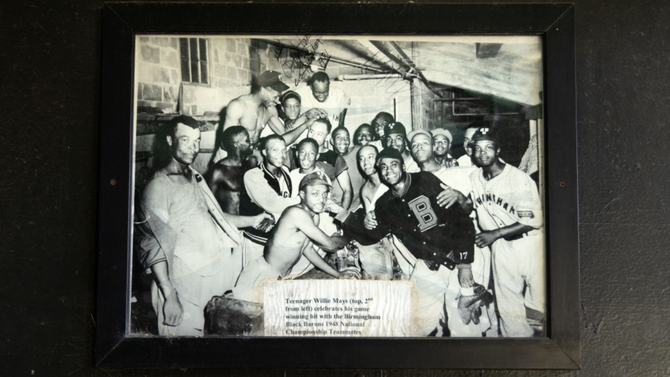

1948

The Black Barons sign 17-year-old outfielder Willie Mays. Because Mays was still in high school, he initially plays only in weekend home games at Rickwood so that he can continue attending school in nearby Fairfield. In his first game as a professional, Mays tallies a pair of hits off Chet Brewer. The expansive Rickwood outfield provides Mays with ample opportunity to display his excellent range and instincts in center field.

Mays’ Black Barons teammate, shortstop Artie Wilson, bats .433 for the season, as the team under player-manager Piper Davis wins the Negro American League title. However, they succumb yet again to the legendary Homestead Grays in the Negro League World Series. The clinching Game 5 at Rickwood stands as the last Negro League World Series game ever played.

This year also occasions Rickwood Field’s all-time seasonal attendance record, as 445,926 fans descend upon the park’s six ticket windows and pass through the turnstiles.

This same year, Walt Dropo hits one of the longest home runs in Rickwood history. Estimated at 467 feet, Dropo’s blast goes over the wooden scoreboard.

1950

Red Sox legend Ted Williams homers twice in his first Rickwood Field appearance.

At one point during the 1950 season, Barons first baseman Norm Zauchin pursues a foul ball into the seats, and he falls into the lap of a woman seated on the first row. Introduction made, Zauchin and the woman will be married two years later.

The Dugout Restaurant is added to the Rickwood grounds. Occasional reputation will have it that the Dugout is only place you can buy beer on Sundays in Birmingham.

June 1950

The New York Giants sign Mays.

1954

Toni Stone, the first woman to play professionally on a predominantly male team, plays at Rickwood for the first time.

Stan Musial playing at Rickwood hits a towering homer over the scoreboard in right field.

Charley Pride, later to become a famed recording artist and pioneering member of the Country Music Hall of Fame, pitches the 1954 season for the Black Barons.

Early 1960s

The Black Barons, in essence reduced to a barnstorming existence by this stage of post-integration baseball, begin to wind down operations. While allowing that “details are sketchy,” the Negro Southern League Museum in Birmingham pegs 1962 as the Black Barons’ final season.

Late 1961

The original Barons cease operations under owner Albert Belcher following the 1961 season, thus leaving Rickwood without an affiliated team. The racist Jim Crow laws of the South are to blame, as the move comes after Major League Baseball in November announces a mandate that all affiliated minor-league teams must integrate by 1962. However, a Birmingham ordinance forbids it. Section 597 reads in part, “It shall be unlawful for a Negro and a white person to play together or in company with each other in any game of cards, dice, dominoes, baseball, softball, football, basketball or similar games.”

1964

Belcher persuades Kansas City A’s owner Charlie Finley, who hails from the area, to locate his club’s Double-A affiliate in Birmingham at Rickwood Field. That year, the revived Barons field the city’s first integrated baseball team. Belcher also takes down the chicken-wire barrier in the stands that had previously separated Black fans from white fans.

One thousand seats from the soon-to-be-razed Polo Grounds in New York are purchased and installed in Rickwood Field. They will remain in use until 1980.

Mid-1960s

Not long after the Braves’ relocation from Milwaukee to Atlanta in 1966, Hank Aaron and his Braves teammates begin playing regular exhibitions against Southern League All-Stars at Rickwood. This lasts until the mid-1970s, when Aaron is traded to the Brewers and later retires from baseball as the all-time Home Run King.

1967

Finley renames the Barons as the Birmingham A’s.

April 22, 1967

Reggie Jackson’s most memorable Rickwood home run, a walk-off grand slam, soars over the fence in right-center that’s 390 feet from the plate. Many in attendance will attest that Jackson’s homer is still rising as it leaves the park.

1975

Finley moves the A’s Double-A affiliate from Birmingham to Chattanooga.

1978

Rickwood becomes the home field of the University of Alabama-Birmingham baseball team.

1981

Southern League baseball returns when the Montgomery Rebels, affiliate of the Detroit Tigers, move to Rickwood and become the latest version of the Birmingham Barons. Following the 1987 season, the Barons, by then under the aegis of the White Sox, move to the Birmingham suburb of Hoover.

1985

The Rickwood Field outfield dimensions undergo drastic changes. The left-field fence is brought in from 405 feet to 325 feet. The distance to center field is reduced from 470 feet to 393 feet. Right field is modestly adjusted from 334 to 332 feet. As well, the seating capacity is reduced to 10,400.

Sept. 9, 1987

The Barons fall to Charlotte in the second game of the Southern League title series. The loss ends the Barons’ time as Rickwood’s regular tenant.

Late 1980s

The City of Birmingham takes ownership of Rickwood Field. Baseball games between city high schools begin to be played at Rickwood.

1991

The demolition of Comiskey Park in Chicago makes Rickwood Field the oldest ballpark in the U.S.

1992

After the venue gradually falls into disrepair, a group of locals forms the Friends of Rickwood organization and makes their mission the restoration of the field. The effort is helped greatly by the filming of the Tommy Lee Jones film “Cobb,” the baseball scenes of which were shot at Rickwood. The film crew’s refurbishments of Rickwood go a long way toward accomplishing the goals of the Friends of Rickwood. One of the biggest early projects is reinstalling the classic drop-in-scoreboard.

In the coming years, an increasing roster of high-school, junior-college, college, and police-league teams will play in Rickwood on a regular basis.

Feb. 1, 1993

Rickwood Field is added to the National Register of Historic Places.

1996

The Barons return for the inaugural Rickwood Classic against the Memphis Chicks. The annual minor-league game at Rickwood features vintage uniforms and the feting of former Barons players.

The television movie “Soul of the Game” uses Rickwood Field in multiple scenes.

Aug. 18, 2010

Rickwood Field celebrates the 100th anniversary of its opening. It becomes the first U.S. ballpark to reach that milestone.

2013

“42,” a Jackie Robinson biopic and Chadwick Boseman vehicle, features Rickwood Field in several scenes.

2018-19

Antique street lights are added outside the park along 12th Street to recreate the feel of the park’s 1940s glory days.

June 20, 2023

MLB announces that on June 20, 2024 the St. Louis Cardinals and San Francisco Giants will play a regular-season game at Rickwood Field. The event is scheduled around Juneteenth, which annually commemorates the end of slavery in the United States. As well, festivities “will include a variety of activities as a tribute to the Negro Leagues” and Mays himself, according to MLB.

“I can’t believe it,” Mays says in a statement at the time. “I never thought I’d see in my lifetime a Major League Baseball game being played on the very field where I played baseball as a teenager. It has been 75 years since I played for the Birmingham Black Barons at Rickwood Field, and to learn that my Giants and the Cardinals will play a game there and honor the legacy of the Negro Leagues and all those who came before them is really emotional for me. We can’t forget what got us here and that was the Negro Leagues for so many of us.”

It is to be the first ever major-league regular-season game played in Mays’ home state of Alabama.

Sources: AL.com; Baseball-Reference.com; EncyclopediaOfAlabama.org; Green Cathedrals by Philip J. Lowry; MiLB.com; MLB.com; National Register of Historic Places, Database and Research; the Negro Southern League Museum; “Rickwood Field Features Baseball’s Past and Present,” by Bruce Markusen, BaseballHall.org; Rickwood.com; SABR.org; “Take Me Out to the Ball Park: The Restoration and Revitalization of Rickwood Field,” by David M. Brewer, Historic Preservation Education Foundation; wvtm13.com

The post Rickwood Field’s legendary history: How Willie Mays and the Negro Leagues made the iconic stadium home first appeared on CBS Sports.