Public ownership works for some of world’s best sports teams — is there a future for the idea in America?

Written by CBS SPORTS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED on June 12, 2024

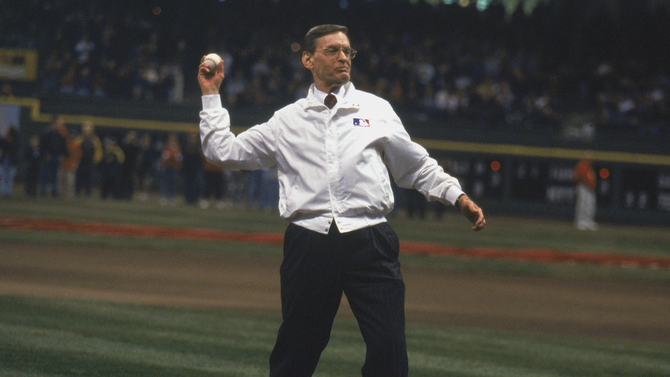

Mario Cuomo had a revolutionary idea. It was the summer of 1990 and the New York governor, perhaps using the sense of anticipation he sharpened as a minor-league outfielder, believed he could get a jump on a play before it developed. “He does not want to sell,” he told reporters. “He’ll do anything to avoid that and I hope he can. But if he decided to sell, I wish he would come to us.”

“He,” in this case, was George Steinbrenner, the owner of the Yankees.

At the time, Steinbrenner was the subject of an ongoing investigation by Major League Baseball commissioner Fay Vincent after it had been discovered that he had paid a gambler to provide incriminating evidence about outfielder Dave Winfield. Steinbrenner would soon be permanently banned from partaking in the Yankees’ day-to-day operations. (He would be reinstated years later.) All possibilities appeared to be on the table when Cuomo floated his trial balloon, including Vincent forcing Steinbrenner to sell the franchise. In that scenario, Cuomo wanted the state of New York to be the first prospective buyer in line.

Cuomo considered the Yankees to be one of the best investments New York could make. He estimated the team made a 35% profit, and was “eminently financeable” for the municipality. (One of Cuomo’s charges believed that the Yankees made more than $50 million in revenue before selling any tickets or concessions.) Cuomo reasoned that buying the Yankees would anchor them in place — an unthinkable concern now, but New York wasn’t long removed from losing the Giants, Nets, and Jets to New Jersey over an eight-year span. “You don’t think they have their eye on the Yankees?” he asked rhetorically.

What happened next will feel familiar to anyone who follows professional sports: Steinbrenner rejected Cuomo’s advances, and turned the governor’s fear into leverage. He then turned that leverage into public funding for a new stadium. The arc exemplified the power imbalance between the billionaire franchise owners and the cities they claim to represent, laying bare how private ownership is often a losing proposition for communities. No market, not even the largest in the country, is immune to the whims of an unsatisfied billionaire.

The Yankees may not have been for sale, but that didn’t mean they were closed to bidding. Steinbrenner was receptive to a different kind of transaction: a relocation to New Jersey once the Yankees’ lease expired in 2002. New York’s attendance had declined four years in a row. That the Yankees had finished no higher than fourth in those seasons was irrelevant to Steinbrenner. He blamed the drop on the neighborhood surrounding Yankee Stadium, specifically the poor parking infrastructure and the perception that it was unsafe. (A Yankees executive would resign in 1994 after calling the children in the predominantly non-white neighborhood “monkeys.”) Steinbrenner demanded a new stadium in a more desirable location — the history contained at The House That Ruth Built be damned. “The Yankees have long played in the Bronx. By the same token, that’s not going to cut it,” team counsel Melvyn Leventhal said. “That’s not enough to keep the Yankees in Yankee Stadium.”

Three years after wanting to entrench the Yankees in New York, Cuomo could feel the club slipping away. He admitted in September 1993 that he believed the team intended to relocate. So began a standoff between the Yankees and New York. Steinbrenner swatted down more than a dozen proposals from the government, including public funding offers to renovate Yankee Stadium and the surrounding area. Nothing would sate Steinbrenner’s desire for a new stadium other than that very thing — though that didn’t stop him from seeking additional benefits along the way. “He’s trying to get higher paybacks, more benefits, more luxury boxes, executive boxes, an even better deal on rent — let’s all write him a check,” Borough President Fernando Ferrer said in 1994. “This is part of an annual ritual. He always gets like this every June and everybody writes about it like it was handed down directly from Mount Sinai.”

Cuomo, Ferrer, and others may have clocked Steinbrenner’s avarice for what it was, but they went along for the ride anyway — the way countless elected officials have over the years. They lacked options. They couldn’t buy the team, or force Steinbrenner to sell to a more reasonable owner (should such a thing exist). If they called Steinbrenner’s bluff and he moved the Yankees to New Jersey, they stood the risk of harming their self-interests. Either way, Steinbrenner was positioned to win, the community to lose.

After several years and countless back-and-forths, New York acquiesced and reached an agreement in 2001 to build a new Yankee Stadium. That deal would be voided by incoming Mayor Michael Bloomberg, but another deal would then be reached in 2006. The final cost to the public exceeded $1 billion dollars, according to Neil DeMause of Field of Schemes. “It is a shame to have to depend on a George Steinbrenner to sustain a great civic inheritance, but that is where we are,” wrote David Remnick, then a staff writer for The New Yorker, in August 1993. Remnick has since taken over as the publication’s editor, but the predicament he bemoaned remains in place.

The spat between Steinbrenner and the state of New York feels both anchored in the past and unmoored from time. Many of the central figures have died, and the new Yankee Stadium is already 15 years old. The dynamics at play between billionaire owner and community, and the tactics used when their interests clash, feel unnervingly current. Major-league markets are different in every way, from their geography to their demographics to their traditions. The one constant is so plain, so unremarkable: They all must suffer a billionaire or corporate owner. To accept that is to accept that the day will come when the owner’s interests clash with the community’s. Once that happens, the owner is likely to channel their inner Steinbrenner and say to the city: Give me what I want, or else.

Must it be this way, with billionaires using these teams — these commodified civic inheritances — as bargaining chips against communities? Informed onlookers and the broader sports ecosystem suggest the answer is no. There is an alternative, the public model, that centers fans and communities over billionaires. Variations of this model, along with its merits, can be found everywhere: from some of the top foreign soccer leagues to the domestic minor leagues — everywhere, it seems, other than the American major leagues.

The main difference between the private and the public ownership models can be surmised as such: Under one, teams are run like businesses; under the other, they’re run like public goods. Private owners demand profit. They’re willing to do whatever it takes to make the number go up, even if that means fielding a poor product or threatening the community with relocation. Public ownership does away with the unchecked profiteering, as well as with the relocation threats — the team is owned by the municipality it resides in, after all. That is not to say that profit is not a goal, it is merely not the only priority; besides, the public model demands greater transparency and democracy when it comes to a team’s finances.

The public model may be a foreign concept to the average American fan accustomed to their favorite teams being held by an individual or corporate entity. Those figures have long since convinced fans that they — the owners themselves — are crucial to the operation; why else would they be the first ones to lift the trophy when their teams win a championship? Yet there’s ample evidence abroad demonstrating that the billionaires who run America’s major-league teams are often the least important part of the machine.

Take the recent Champions League final between Real Madrid and Borussia Dortmund, a matchup that featured zero external or corporate owners, as evidence that it doesn’t take a billionaire to build a winner. For more evidence, consider those teams’ respective home leagues.

Over in Germany, the Bundesliga (the country’s top-flight soccer league) requires every club to own at least 50% of its shares, plus one more. That way, there’s no possibility of investor overreach. In fact, the Bundesliga outlawed private ownership entirely until 1998. There have been exemptions for investors with longstanding ties to a club, though those are all together rare. Bundesliga’s difference in philosophy shines through in various ways, including how the business side of the game is talked about and managed.

“The German spectator traditionally has close ties with his club. And if he gets the feeling that he’s no longer regarded as a fan but instead as a customer, we’ll have a problem,” Hans-Joachim Watzke, the CEO of Borussia Dortmund, said in 2016. “An investor in Dortmund would soon turn 28,000 standing places into 15,000 seats, which would guarantee several million euros more per year. But I don’t want the fans to be milked as is happening in England.”

Compare and contrast that quote to what a former Los Angeles Angels executive said in 2015: “We may not be reaching as many of the people on the lower end of the socioeconomic ladder, but those people, they may enjoy the game, but they pay less, and we’re not seeing the conversion on the per-caps.”

Because Bundesliga teams aren’t hellbent on taking every dollar from their supporters, their tickets remain cheap by American standards. A Dortmund fan could have purchased a season ticket last year for the equivalent of $260, or just over $15 per game. The lowest average list ticket price among MLB teams in 2023 belonged to the Miami Marlins, at $69, according to Statista. To think, Dortmund’s tickets are on the expensive side for Bundesliga.

In Spain, Real Madrid and FC Barcelona are among four publicly owned clubs. Members, called socios, endure lengthy waiting periods for the opportunity to pay an annual fee (around $160) for entrance. The perks include voting privileges and an opportunity to land season tickets. The socios are so fervent about this arrangement that FC Barcelona’s have pushed back against potentially selling shares to a private investor to reduce the team’s debt from years of runaway spending. (Real Madrid, for their part, just announced their signing of Kylian Mbappé, suggesting blockbuster acquisitions are not only for billionaires.)

A Spanish law banned public ownership in the ’90s (Real Madrid and Barcelona were among the four teams exempt from the law), but it wasn’t because the teams were struggling to field a good product. As attorney Stephen R. Keeney wrote in 2021 for the Society for American Baseball Research journal, La Liga’s four publicly owned clubs had won more than 75% of the league’s titles. Those La Liga teams and their Bundesliga peers have combined for 29 European Cup and Champions League finals — that includes Madrid’s win over Dortmund.

The public model has led to success in other forms of international football, too. The Canadian Football League features three publicly owned teams: the Winnipeg Blue Bombers, Saskatchewan Roughriders, and Edmonton Elks. (The Elks are currently seeking a private owner after being community owned for nearly a century.) Those three franchises have combined to win 24 Grey Cups since 1958.

Professional sports is a copycat industry. Whenever a team succeeds, everyone else is quick to mine their game for parts they can steal. Clearly, there’s a philosophical limit on that mimicry. While there’s no shortage of instances of American teams looking elsewhere for insight on tactics, development, and training, there’s been less willingness to ape other parts of their operation.

“I think the idea is so foreign to the average American sports fan that there aren’t necessarily well-developed arguments against it, at least not that I’m aware of,” Keeney told CBS Sports in an email. “I think the biggest misconception is just the false, big-picture idea that the private sector is always more efficient than the public sector which is constantly hammered into Americans. It’s a notion that fails the most basic level of scrutiny.”

The best American examples of public- and community-owned teams are found in the minor and independent leagues — be it the Wisconsin Timber Rattlers, who operated as a non-profit through a World War and several league shutdowns until the lost COVID-19 season caused them to sell; the Harrisburg Senators, who were purchased by the city in response to a relocation threat, and were later sold for twice what the city paid for it — as well as with a long-term guarantee the team would remain in place; the Columbus Clippers, the Syracuse Mets, or the Memphis Redbirds.

The Redbirds, for their part, demonstrated that the alternative ownership model, much like everything else, can work until it doesn’t.

Dean Jernigan, the founder of Storage USA Inc., spent more than $8 million to acquire a Triple-A expansion team after Memphis’ previous minor-league affiliate relocated to Jackson, Mississippi. Jernigan then handed the team over to a non-profit foundation that was governed by a volunteer board. They took steps to ensure the board reflected the Memphis community. Bylaws stipulated that half of the board’s members had to be women, and that “the ethnic diversity of the Elected Directors shall approximate, as closely as possible, that of the at-large community.” (Black people have made up more than 60% of Memphis’ population for decades, according to data from past United States Censuses.)

“I’m not an owner,” Jernigan told Fast Company in 2000. “I’m a founder. This team is a community asset. We’ve taken the greed out of sports. We’ve eliminated the greed factor.”

Jernigan and his group were so committed to centering the community that, as Fast Company alleges, they rejected an architect’s idea for using space adjacent to the ballpark for a hotel. They instead made it into a public space complete with art installation. The money that the Redbirds made that was left over after paying for the team’s operation, meanwhile, funded inner-city youth baseball and softball leagues.

There was just one problem with the Redbirds’ vision: It didn’t last.

In what proved to be an overzealous decision, the Redbirds constructed AutoZone Park for $72 million. At the time, it was the most expensive ballpark in minor-league history, though it has since been displaced by Polar Park, home of the Worcester Red Sox. Whereas Polar Park cost taxpayers around $100 million, AutoZone Park required minimal public funding (estimated to be about 10%). The Redbirds relied upon a bond-heavy approach to fund AutoZone Park, and they contractually stipulated those bonds would be repaid using stadium income. For a time, that unusual approach worked. And then, ever so quickly, it did not.

In March 2009, the Commercial Appeal reported that the Redbirds were concerned about declining revenues. They were unsure about their ability to make their next bond payment (they paid around $5 million a year). They were reported to be exploring a modification to their agreement, which, if accepted, would backload the deal. Within months, the Redbirds would default on a payment, triggering a change at the management level. Global Spectrum, a Comcast subsidiary, would take over in July. Weeks later, Global Spectrum conducted layoffs to trim more than a half million from its books.

The youth baseball season, bankrolled by the Redbirds, would be canceled.

“The business model failed,” John Pontius, a financial analyst and former member of the Redbirds Foundation, told the Memphis Flyer in 2010, “in that the debt was way in excess of what could be supported by the revenue of a minor-league baseball team.” Pontius pointed out that most minor-league teams pay rent to their host municipality, ranging from $500,000 to $1 million. The Redbirds, admirable as their approach may have been, were paying much more by virtue of not exploiting their community.

The Redbirds have since changed hands several times. The Cardinals held the affiliate for a while before selling it to Diamond Baseball Holdings, then a property of Endeavor. When the MLB Players Association objected to Endeavor’s involvement because of its proximity to the WME Sports agency division, the Redbirds and Diamond Baseball Holdings were sold to Silver Lake.

For a team that embodied the non-profit ownership model to end up as just another asset in a private equity firm’s portfolio may feel like a sign, a cruel rejoinder from the universe about the shortcomings of other approaches. But, while Jernigan’s vision may have been too bold, it’s worth remembering that there are meaningful differences between minor- and major-league life, both in expenditures and in revenue streams, that could have resulted in a happier ending for the Redbirds. Consider how the only American major-league team that can be classified as publicly owned, the National Football League’s Green Bay Packers, survived the pandemic — and made more money in the process.

The Athletic reported in 2021 that the Packers “turned a net profit of $60.7 million” in 2020, a higher figure than they recorded in either of the previous two years. That was with the pandemic squelching their gate revenue. Yet the Packers made a profit through other means, including the league’s revenue sharing on its national broadcast deal and substantive financial investments. Last July, with the pandemic season in the rearview, the Packers reported a $68.6 million operating profit.

The Packers’ uniquity, well-covered ground, is certain to remain, too. Flip to page five of the NFL’s constitution and you’ll find language that bans teams from pursuing a similar non-profit arrangement: “No corporation, association, partnership, or other entity not operated for profit nor any charitable organization or entity not presently a member of the League shall be eligible for membership.”

To understand why the leagues — and, more specifically, the other owners — reject public ownership is to understand why communities should pursue it.

Andy Ellis, a steering committee member for the Baltimore City Green Party and a 2026 candidate for governor, became a proponent for public ownership last summer.

Ellis, a lifelong Baltimore Orioles fan, had grown apprehensive about the relocation rumors that surrounded the franchise. He didn’t view the scenario as a “seriously credible threat,” he told CBS Sports during a phone interview, but the possibility spurred him to research the dynamics between cities and franchise owners. He found an equation badly in need of balancing.

“I realized that we had an opportunity to change the way that conversation was framed,” Ellis said about an op-ed he wrote last August for a local non-profit news publication. “Because too often it is framed as either give the billionaire owner of the sports team everything they want or the team leaves. I wanted to introduce a third option to that, which is what’s considered public ownership, so that we’re not constantly stuck in that extortion cycle.”

Steinbrenner’s antics during the ’90s provide a useful example of that so-called extortion cycle. The essence of it has an owner leveraging the community for something — oftentimes public funding for a new stadium, but other times more money, more land, and/or more tax breaks — by threatening to move the team to another city. History suggests that such episodes should be viewed as an inevitability of private ownership, not an anomaly. In fact, the practice is so prevalent among the American major leagues that even some owners have expressed open disdain for public funding. “We can better spend that money on firefighters, teachers, and policemen,” Vegas Golden Knights owner Bill Foley said in 2017. “Let’s have the best of that as opposed to building the big stadium.” (Foley also owns stakes in several international soccer clubs, including AFC Bournemouth of the EPL, meaning he knows of what he speaks.)

Too often, owners are viewed as individuals who were merely granted entrance to an exclusive club. That is true, however those individuals were also granted access to a special lever of power — the kind that comes with a massive industry that features a degree of brand loyalty that Coca Cola and McDonald’s can only envy. Those who have that power, particularly in closed systems like pro sports, have the leverage. And if those who have the leverage are willing to use it, whatever that entails, they can reap the benefits.

The kind of people who can afford to become sports owners tend to use their leverage. Billionaires are billionaires for a reason; the extreme acclimation of wealth seldom results from putting one’s financial interests on the back burner. It should be unsurprising, then, when those individuals emphasize enriching themselves — even if it means simultaneously depriving their communities by siphoning taxpayer dollars.

Communities, in turn, are constantly being forced to grapple with two options: Give the billionaire what they want, or risk losing their beloved teams. What often gets overlooked is that the game is rigged in favor of the owners. There’s always a greater demand for teams than a supply of them. Without equity in the teams themselves, communities have little to no recourse. Communities almost have to rely upon the leagues to police their owners, and to prevent them from collectively overreaching. That can be a dicey proposition, particularly when, like in MLB, the commissioner is chosen by the owners — or, as was the case of Bud Selig, is even one themselves.

Whatever you call the cycle — extortion; corporate welfare; the cost of doing Big League Business — MLB teams can credit Selig for teaching them how to perfect the process. Selig’s undeniable skill for obtaining public funding helped shape the league during his time atop the masthead. Back in 2004, Steve Fainaru reported in the Washington Post that Selig had “helped baseball obtain $3.22 billion in public subsidies for 15 new or renovated ballparks — including his own — over the past 12 years.” Selig, Fainaru noted, accomplished that through the use of personal lobbying and both direct and implied threats of relocation.

Selig, who became commissioner on an acting basis in 1992, remained the owner of the Milwaukee Brewers until 2005. Along the way, he secured public funding for Miller Park, deploying strategies that frustrated Wisconsin politicians — to the point that they lashed out. Among them was then-state Senator Michael G. Ellis (R), who said: “Nobody is better equipped to show people how to fleece the taxpayers into building them a new stadium than Allan H. [Bud] Selig. He could write a textbook on how he committed the taxpayers of Wisconsin to build a stadium at no cost whatsoever to the Seligs.”

At least five MLB owners — a sixth of the league — are currently trying to put Selig’s teachings to use by seeking a boondoggle of their own. (The new Brewers owners, by the way, secured more than half a billion in public funds to renovate Miller Park last fall.) The thing about making constant relocation threats is that, at some point, you have to prove that the tongue comes with fangs. Sure enough, current MLB commissioner Rob Manfred will oversee his first (and perhaps what proves to be his only) relocation this winter, when the Athletics move from Oakland to Sacramento as part of a multi-year layover ahead of their arrival in Las Vegas.

The Athletics are just the second team to relocate since the ’70s, following the Montreal Expos in 2004-05. Comparatively, 10 teams migrated between 1950-72. That deceleration hasn’t stopped teams from leveraging relocation to get what they want. To wit, the Athletics were no strangers to the Relocation Threat Boogie, having attempted to finagle a new stadium for decades without avail. Back in the mid-90s, when the Athletics appeared dead set on following the Raiders’ cleatmarks to other pastures, then-Oakland mayor Elihu Harris sought help from superagent Leigh Steinberg, an East Bay native who attended Berkley, to keep the franchise in place.

Steinberg recounted those efforts to CBS Sports, explaining how he and Harris were able to rally together a consortium of local businesspersons to provide a better support system for the Athletics. They also found new owners for the franchise, with Steve Schott and Ken Hofman purchasing the club from Walter Haas in 1995 for more than $70 million.

When it comes to the private ownership model, the road underneath the fleet of U-Haul trucks is often paved with good intentions. When Schott and Hofman sold the A’s a decade later, they sold it to Lew Wolff and Donald Fisher — the father of current managing partner John Fisher. The younger Fisher, who took over the reins in 2016, has since served as the driving force behind the A’s move to Las Vegas. Throughout the relocation process, he showed no apparent inclination toward selling the team instead of taking it from Oakland. (He has, however, shown a warped perspective on the matter, reportedly telling A’s fans last fall: “All that time it’s been a lot worse for me than it’s been for you.”)

Under Fisher’s watch, the A’s have made a quick descent into a potentially long stay in irrelevancy. They’ve traded star after star without receiving commensurate value, and they’ve refused to invest in their roster beyond the kind of trifling veteran additions seemingly designed to fend off a grievance from the MLB Players Association. Add in the executive suite’s dalliance with Las Vegas, and they’ve salted the grounds of a once-proud market.

“I don’t think it’s particularly compelling [when] a team puts a less-than-quality product on the field and plays in an unfriendly ballpark claims, ‘Well, we’re not getting support,’” Steinberg told CBS Sports. He described the Athletics’ failures in Oakland as a self-fulfilling prophecy, comparing it to when the Rams wanted to leave Los Angeles. “They stopped advertising, they stopped community outreach, they gave away Eric Dickerson,” he said, referring to a 1987 trade. “They did all sorts of things to push fans away.”

Fisher was nevertheless rewarded last summer, when Nevada Gov. Joe Lombardo signed a bill granting the Athletics $380 million in public financing. The lesson is clear: private ownership is a winner-takes-all game that pits market against market, fan against fan, governor against governor — and the billionaire in charge of the franchise profits off it all.

A team may wear a city’s name across its chest, but that doesn’t mean the control person always has the community’s interest at heart.

Most fans are likely as indifferent toward their team’s owner as they are the first-base coach. There are, inevitably, some owners who are viewed more favorably by their bases. Those owners tend to be the ones who take a min-max approach: minimal meddling in roster-building operations, but maximum spending in that same area. The trouble with these perceived “good” ownership situations is that they’re fleeting.

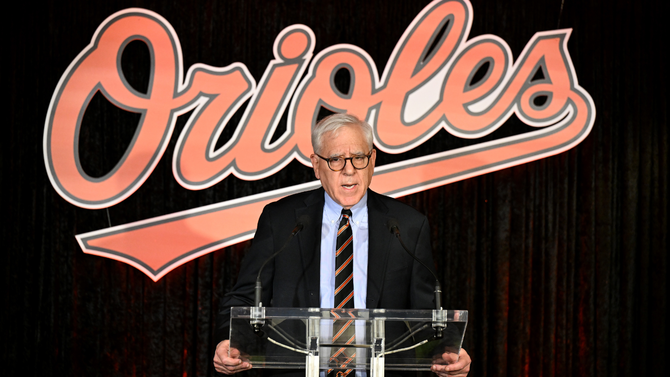

Take the Orioles, the team that inspired Ellis’ call for public ownership. Their recent history reveals the good owner as an unsteady dynamic.

Longtime owner Peter Angelos, who died in March, left behind a complicated legacy. He spent significant money on payroll after taking over in 1993 and his freewheeling ways helped the Orioles reach consecutive American League Championship Series in 1996 and 1997. He was admirable in other respects, too, like refusing to use replacement players during the 1994-95 strike — that despite the league threatening to fine him with every passing game and/or perhaps strip him of the franchise entirely. Angelos’ approval rating cratered in the years to come, as he became known as a meddler who was too involved with baseball operations decisions, oftentimes to the team’s detriment.

The Angelos family sold the Orioles to Baltimore native David Rubenstein just ahead of the start of this season. In time, the Orioles faithful may feel that moment was akin to winning the fan lottery. That’s because, even when a community lucks out with a generous owner, an early Angelos or potentially a Rubenstein, it’s a matter of time before the private model necessitates the same must hold true of the owner’s successor: be it their children, their minority partners, or an outside party. The community, generally the one constant in the equation, has no actual input in the succession plan.

Regardless of the final verdict on Peter’s ownership, this much is certain: The Orioles entered a state of flux once he became incapacitated. Peter’s sons, John and Louis, were soon entangled in a feud that saw John take control and Louis take legal action. Louis alleged as part of his lawsuit that John intended to move the Orioles to Nashville, Tennessee. (The lawsuit was settled last year.) Whereas Peter usually fielded league-average or better payrolls, John’s time as control person saw the Orioles bottom out financially: they haven’t ranked higher than 26th in Opening Day payroll since 2018. The Orioles have made a nest near the top of the standings all the same, but one wonders if their ascent would have occurred quicker had the Angelos heirs invested more resources.

At the same time the Orioles were refusing to spend money on their big-league roster, they were using the impending expiration of their lease to extract more value from the city they’ve called home since 1954. In December, the Orioles signed a new long-term lease with the city of Baltimore to remain at Camden Yards for the foreseeable future. Negotiations ran close to the deadline and, at one point, a deal was delayed when State Senate President Bill Ferguson expressed concerns about a provision that granted the Orioles land development rights over taxpayer-owned property. (The Orioles, by the way, also received access to $600 million in bond money as part of the lease renewal.)

Teams have started labeling these agreements as “public-private partnerships”; all evidence indicates the name is the only point in these arrangements where the public comes first.

Back in the ’80s and ’90s, the city of Pittsburgh authorized multiple loans to keep the Pirates solvent and in town. The terms of the first loan, worth $20 million, stipulated the team would have to repay the city only if they showed a “positive cash flow” at any point over the term. Predictably, the Pirates showed contrived loss after contrived loss using legal and accepted accounting tricks, all the while racking up playoff berths and establishing new records in both attendance and payroll. The Pirates grew emboldened when they went back for more public funding. The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reported in July 1994 that the Pirates did not immediately accept the city’s offer for an $8 million loan, befuddling and borderline insulting the politicians trying to help them out. Instead, they requested the stadium authority also renegotiate their lease terms for Three Rivers Stadium — they sought $6 million to $7 million in relief.

The Pirates’ quest for public funding didn’t end there.

Over the ensuing years, the Pirates were rumored to be of interest to a businessperson who intended to relocate the club to Virginia. Instead, the Pirates would be purchased in 1996 by Kevin McClatchy, a local willing to keep the team in Pittsburgh. There was a catch, of course. McClatchy’s efforts for a new publicly funded ballpark hit a snag when Pittsburgh voters rejected the project. It didn’t matter. Local officials circumvented voters’ wishes, forcing through public funding several times greater than what the Pirates contributed to the construction of PNC Park. Subsequent investigations have found that the Pirates rely heavily on the public bearing the financial burden for stadium repairs. A publicly owned stadium and a privately owned team represents the worst possible combination for communities: they may as well possess a reel without the rod, a tire without the bike, or an electric guitar without the amplifier.

Those same Pirates, by the way, wouldn’t record a winning season between 1993 and 2012. It made no difference to their bottom line. Leaked documents from 2007-08 showed that the club, though a reliably poor product, was highly profitable. To paraphrase Ellis: teams are quick to subside losses and privatize profits. Any city that pushes back on that arrangement is liable to feel the consequences.

Owners are able to pull off these, at times, hamfisted schemes because of the weird space their teams occupy in the community’s ecosystem.

Steinberg can speak to the broader dynamic because, by the time he became involved in Harris’ plot to save the Athletics, he was a seasoned opponent of relocation. He had previously partaken in campaigns to anchor the Giants in San Francisco (a success) and the Rams in Los Angeles (a temporary success, by his own admission). Steinberg attributed his passion for the subject to the social contract between professional sports franchises and the communities they’re supposed to represent.

“Professional franchises claim to be in part a civic treasure, like the Golden Gate Bridge,” Steinberg told CBS Sports. “They claim to be a private business but they deserve geographical support, so they’re your Oakland A’s. So, if that is the theme, that this is sort of the responsibility of fans to go even if the team is leaving, to provide loyalty — and that takes many years to build up — then to rip a team out of the heart of loyal fans strikes me as very destructive for professional sports.”

Ambrose Bierce might have quipped that teams define themselves as civic goods when they’re asking for public funding, and as private businesses when they don’t receive it. Removing the dichotomy from play seems like the best route forward, albeit one that’s likely to be contested.

Cuomo wasn’t the only notable figure in MLB’s circle thinking about public ownership in 1990. The idea was gaining steam, from coast to coast and even beyond the northern border. The previous fall, Joan Kroc had attempted to give the city of San Diego both the Padres and a $100 million public trust on her way out of the baseball business. Meanwhile, in Montreal, the city had invested millions upon millions to keep the Expos in town, all the while failing to gain any equity in the franchise. In both cases, it was the other owners who had kept the municipalities out of their closed club — in no small part because they feared the public scrutiny that would come with the disclosure of the team’s finances.

“The owners in the top leagues are all billionaires or close to it,” Keeney told CBS Sports. “That small group of Americans has a level of class consciousness and solidarity that factory workers could only dream of.”

As it turned out, those fears may have been unfounded. A dirty secret of professional sports is that you can already find financial information concerning two franchises: the aforementioned Packers, and the Atlanta Braves, who are owned by a publicly traded company and therefore must disclose their finances. Anyone with internet access can learn that the Braves generated $641 million in revenue last year, and that the Braves showed an operating profit before depreciation and amortization of $38 million. But, through perfectly legal tricks like the Roster Depreciation Allowance, the Braves were able to report an operating loss of $46 million. The Braves subsequently increased their payroll by another $20 million over the offseason — hardly the sort of a thing a team in any actual financial distress would do.

Public knowledge of the Braves and Packers’ financial situations hasn’t prevented their privately owned peers from readily turning on the public-funding spigot. It hasn’t stopped some fans and media members from uncritically repeating talking points from teams about losing money or being unable to afford star players, either. What it has done is highlight that the real risk public ownership poses for private owners is revealing how little they matter. The leagues, through careful and often calculated moves, are simply too big to fail and the individual teams print money even when they’re unable to sell tickets or concessions. The owners, these contemporary Lords of the Realm, may fancy themselves as business geniuses, but any replacement-level suit could make many quick bucks from a sports team.

And so, it stands to reason, could municipalities — if they were permitted a seat at the table.

Unlike the NFL, MLB has seemingly offered no official position on the public model; you won’t find any references to non-profit ownership in the league’s constitution. In the past, MLB has even encouraged minor-league franchises to embrace the communal model, suggesting the league views it as a legitimate approach, at least in the minors. Back in 1990, when Cuomo floated his trial balloon, a league spokesperson named Jim Small responded by saying “it could be possible.” Small declined to elaborate further, pointing out that the Yankees weren’t actually for sale.

Fans and politicians tired of the private ownership model and all it entails should rephrase Small and ask themselves: could it be possible? Is public ownership of an American major-league team doable?

While pro sports owners appear to have all the leverage under the current conditions, the irony is that motivated government officials could change all that if those owners refused to let them in. That shift could come in a few forms, including the usage of eminent domain laws and/or an attempt to strip MLB of its antitrust exemption — the longstanding reason that the league is allowed to operate as a legal monopoly.

Eminent domain has been used and debated before in sports matters, albeit most famously in the opposite direction. Back in the ’50s, Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley purchased land from Los Angeles that had been seized from Mexican American communities using eminent domain laws. (Ironically, it would be O’Malley’s son, Peter, who would play a role in preventing Kroc from giving the Padres to San Diego.) O’Malley would build Dodger Stadium on the site of those old family homes.

Decades later, the city of Baltimore tried to use eminent domain laws to prevent the Colts from relocating to Indianapolis. The Colts, however, snuck away in the middle of the night before Baltimore could seize control. When Oakland attempted to do the same to the Raiders, the California Supreme Court stated that “providing access to recreation to its residents in the form of spectator sports is an appropriate function of city government.” As DeMause reported in 2014, it’s unclear if eminent domain would be an effective tool anymore. Of course, there’s only one real way to find out.

The other route that government officials could take is removing MLB’s antitrust protection. Sources who spoke to CBS Sports for this piece were mixed on how effective those efforts might be. One pointed out that MLB did settle a lawsuit with minor-league players last year, suggesting they would prefer to avoid potential legal threats to their exemption. At the same time, politicians have long made empty threats toward the league’s antitrust protection without ever acting on it.

Ellis, though a proponent of public ownership, would prefer to avoid going down either route.

“I’d love to spend our time not thinking about how we seize the team from [Rubenstein and his family] in a couple of years, but instead thinking about how we get him on board with this,” Ellis told CBS Sports. “What if his legacy and gift to the city of Baltimore — just like the Carnegies left us libraries and opera halls and things like that — is that he helps us figure out how the city and the state can own the team?”

The team would become a community treasure — and so, in a sense, would an owner who proved they were committed to their city, even if it meant removing themselves from the equation.

Of course, it’s fair to wonder if a city or state should be using precious budget space on a team. Franchise costs have continued to rise, to the point that the Orioles sold for $1.7 billion and both the Kansas City Royals and Miami Marlins cleared $1 billion. Is making that kind of investment really in the best interest for a community that could instead use that money to fund education and other public services?

Probably not, but let’s face it: the same philosophical question is an argument against building stadiums for billionaires — and those still get built all the time, even in smaller markets like Milwaukee and Pittsburgh. There’s no indication the stadium swindle is going away, despite being wholly unpopular with the general public. Back in April, Kansas City voters rejected a sales tax measure that would’ve funded a new ballpark for the Royals and renovations for the Chiefs; as it turns out, there’s a reason teams increasingly try to find a way to public funding that doesn’t allow the community to have a say in the matter.

Economists have long been skeptical that sports stadiums even help local economies, largely because of the substitution effect. Some studies have even found that economies improve after losing their sports team. It’s not as though funding stadiums is becoming cheaper, either. Consider the situation playing out in Chicago, where the Bears are seeking $2.65 billion in public funding for a new stadium. Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker has scoffed at the campaign, noting how strongly his constituencies oppose it and how unfavorable the terms are for the city. (The Bears’ proposal would not see the team share any of the stadium revenue generated from concerts and other events with the city.)

Still, life needn’t be purely rational or efficient — it’s OK to find value in aspects of the community that may not be economic drivers; if communities are going to make substantive investments in sports, however, then it’s better to possess the team than the stadium. That’s especially true as public subsidy costs creep upward — compare the Bears’ stadium ask of $2.65 billion to the $2.475 billion it cost Steve Cohen to buy the New York Mets in 2020. There’s no question which of those is the more valuable asset.

If Mario Cuomo had still been in charge when the Mets were placed on the market, perhaps he would’ve attempted to secure the franchise for New York. As it stands, public ownership in the American major leagues remains a theory rather than a reality. Changing that will necessitate a boldness, in approach and vision, that can’t be easily shaken by the efforts of the private owners.

The public ownership model may not be perfect itself, it would serve as a panacea for some of what ails communities when it comes to professional sports. Perhaps that is what would finally shake the persistent feeling that the community is more of a financier than a partner to its local sports franchises. Realistically, municipalities owning sports teams is about more than making the name on the front of the jersey mean something; it’s also a sensible business decision. The profits generated by teams could be repurposed to improve the quality of life in the area, rather than deployed by a billionaire on a new yacht, a damaged painting, or, even, another sports franchise.

It would put the ball where it belongs: in the hands of the community.

“If teams are public goods, then profits they generate are used according to the wishes of the community, instead of the wishes of a few wealthy individuals,” Keeney told CBS Sports. “And that very concept of economic democracy runs counter to the very existence of their wealth.”

The post Public ownership works for some of world’s best sports teams — is there a future for the idea in America? first appeared on CBS Sports.